Organizers

You Show Show Notes

#over / #notover … no one decides

Co-Learning requires Confronting Fear, Taking Risks, Embracing Error, and Encouraging Agency By Howard Rheingold

Co-Learning requires Confronting Fear, Taking Risks, Embracing Error, and Encouraging Agency

Co-learning, by my definition, involves, above all, giving learners real agency. That means making room in your preplanned curriculum for what the learners want to do, then encouraging learner agency by telling them to think about projects that THEY want to do, learning activities and texts THEY want to pursue. It also means that the instructor must take a risk before other learners can follow suit — and for educators, that’s where the fear is first confronted. I starkly remember the fear I felt when I first faced rooms full of (in my case, college) students. I was confident in my knowledge of the subject matter. But as a novice instructor with no training, I was afraid of taking the risk of letting the students know how much I didn’t know. Agency requires vulnerability — it’s always safer to follow instructions than to invent your own — and the system of authority embodied in the rows of desks facing the lone standing teacher provides a ready-made script for learning that everyone in the classroom understands: For students, the script only requires them to sit and listen, take notes, attune themselves to what they might be tested on, replay what they’ve learned when called upon. In the traditional script, only the boldest student directs questions oftothe instructor. But unless the instructor models as well as encourages the students to reveal what interests them and to drop their fear of exposing what they don’t know, the reward for confronting these fears — a real sense of agency by learners, accompanied by the enthusiasm that comes from pursuing your own curiosity, will elude the would-be co-learners.

I have never gone this far, but high school teacher David Preston confronts the fear and agency issue by telling his students to decide among themselves what is really important to learn — then physically leaving the classroom with no further instruction. What kind of courage does it take to throw your learners in the water without telling them exactly how and where to swim? However, after spending hours talking with David and his students and other extraordinary high school teachers such as Don Wettrick and Amy Burvall, and after taking my own attempts to give learning power and responsibility to students, I can say with the authority of a practitioner that an instructor’s courage to grant radical agency to learners will often (not always! there’s the risk!) pay back spectacularly.

But what if it doesn’t work? That insidious question is powerfully and frequently reinforced by our educational institutions’ phobia about “failing” (a needlessly pejorative word for the kind of error that is often necessary for trial-and-error learning). In many commercial enterprises, management has to struggle with the conflict between succeeding-by-not-failing and innovating-by-taking-risk. Students of computer programming and electronic circuitry know that code and circuits most often don’t work as soon as they are assembled, but require a search for and repair of the error. Often, this involves knowing how to search for specific conversations online, to engage in them, and to call upon networked knowledge. Always, it involves a willingness to look for what you’ve done wrong. As any programmer or tinkerer can tell you, when code finally runs or a circuit finally does what it was intended to do — especially after a frustrating debugging process — the rush of triumph and achievement seals what they’ve learned far more effectively than fear of failing on a test.

In the classroom, I try to model error-embracing as soon as I can. I have a good tool for doing this. Because social media has been the subject matter of my courses, it only makes sense to use (and reflect upon) social media in our co-learning process. So I try and demonstrate all kinds of new apps and platforms in class, and push the media until something goes wrong. At that point, I remind them of what has become something of a cliche of mine — “you aren’t exploring the edge if you don’t fall off from time to time” — and start systematically thinking aloud about where the problem lies, whether and how it can be fixed, or what workarounds can help accomplish my goal, whether or not the technology error can be repaired. Errors should be seen as the first clues in an inquiry, and that inquiry must include a practiced skill of looking for where the learner made a mistake.

I’ve been told — and experienced first-hand as a (failed) entrepreneur — that one reason why Silicon Valley venture capital-fueled innovation has been so successful, and why it has been difficult to duplicate it elsewhere, is that failure is not shameful. The day after the news got out that I had cratered my early dotcom, I started getting calls from potential investors in my next one. There’s a good reason for that. You learn a lot when you crater a start-up. But in other parts of the world, failure is shameful. Failure is the end — not a way-station on a learning journey that ends in success.

I asked myself how I could reduce the most useful actions to encourage co-learning to the smallest number of words. I came up with “confront fear, take risks, embrace error, encourage agency.” You don’t have to dive in head first. Dip your toe in the water. Confront your fears in small pieces. Experiment with small errors, take small risks, give students small amounts of agency. Then when the world doesn’t end and some students actually exhibit excitement about their agency, get a little bolder. Co-learning is about learning what works on and with your students through trial-error-revision-reflection every day, every new term, every year.

The Blog Talk Garage is Open

Connected Course Webhosting/Hoteling

A Conversation with the Mother of the Motherblog

Is That Pigeon Hole Half Empty or Half Full?

It’s All About the Do

Co-learning About Co-learning

Co-learning About Co-learning

I believe that co-learning is what made us human in the first place, and if we are to agree upon what it means to be more human and endeavor to achieve that goal, our ability to co-learn will be crucial. Professor Rob Boyd of the Arizona State University School of Evolution and Social Change puts it this way:

Unlike other organisms, humans acquire a rich body of information from others by teaching, imitation, and other forms of social learning, and this culturally transmitted information strongly influences human behavior. Culture is an essential part of the human adaptation, and as much a part of human biology as bipedal locomotion or thick enamel on our molars.

When we talk about technology and the way we use it, we’re talking about the tool — the hardware, software, and systems that enable it to work — and at the same time we’re talking about mindsets and cultural norms, the psychosocial aspect of the tool, and also talking about the institution framework within which the tool is used. Our species’ capacity for learning, together with what humans have discovered and taught each other — in other words, culture — is brought together in the institution of the school.

Alphabets, chalkboards, textbooks, laptops, lectures, exercises, tests, routines are tools for learning that can be used to enforce the kind of industrial-era mechanization of behavior decried by critics such as John Taylor Gatto andIvan Illich. Social learning and knowledge technology can also be used in an institutional framework where student-centric and peer-to-peer practices are more dominant. Co-learning requires a kind of reflection by students and teachers about how exactly they are going about their individual and group learning. Part of co-learning is questioning what we mean by the term.

I stumbled onto the power of calling us all co-learners at least some of the time, rather than making the teacher-student distinction all the time. When I email the coming week’s assignments to my university students, I always addressed them as “esteemed students.” When I started experimenting with a different institutional setting, , I began my first email to my first totally online class with the salutation: “Esteemed co-learners.” Talk about word-magic! Although I explicitly aimed for a learning community, those who had chosen to learn with me online (rather than, say, selecting my class as one of their required electives) took the term seriously for the beginning.

So what did we decide we meant by co-learning? First, we had to listen to each other so we could enhance each other’s learning as well as our own. Second, we all had to participate. Lurkers (or less harshly, “read-only members”) are a healthy part of all kinds of online groups, but co-learning requires that each participant contribute — through blogging and commenting on each other’s blogs, building conversations in the forum that explored our texts and mutual interests over a period weeks, by collaboratively editing a lexicon on the course wiki, and other activities initiated by the convening instructor (me) or by any other co-learner. What started out as a happy accident of wording turned into something magical.

I’ve learned that the magic doesn’t happen all the time, and I’ve been trying to understand what the critical factors might be. I’ve identified a few factors (and I’m sure there are more): the presence of two or three “lead learners” who are willing to jump into an online conversation the night after our class meeting rather than the night before our class meeting, activities that enable the learners to interact with each other in twos, threes, and fours, and my own responsiveness to how student co-learners are exercising their power to take more responsibility for their learning.

Co-learning is not just about collaborative projects and sharing resources, pointing others to resources, participation and conversation. It’s also about a re-negotiation of how much authority teachers and students can exercise. I remember how it felt when I started telling students that I trusted them to help shape the curriculum and that in exchange for gaining this power they were going to take more responsibility for each other’s learning. It was scary! First, could I really trust them to know what to do? Equally, it was frightening to admit how much I was learning. Fortunately, my courses deal with all manner of social media technologies that provide me with early opportunities to model failure, debugging, and an unashamed learning attitude toward error.

This week in Connected Courses, we’ll explore the why to, how to, and what does co-learning mean, anyway?

Looking for Light/Looking for Ideas

Colearning communities can benefit from reflection on the fly

Colearning communities can benefit from reflection on the fly

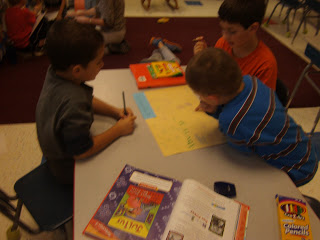

source: mrspelkeyssecondgrade.blogspot.com

In my definition, co-learning involves a re-orientation of each learner from purely individual acquisition of knowledge toward a process of sharing learning and sense-making with each other learner — peer-learning and peer-teaching at the same time. Co-learning also means that the teachers learn along with and from other learners in the same course.

Do enough participants in Connected Courses #ccourses want to continue the conversation after the final unit is completed? Before community can emerge from a longer-term weaving of reciprocities and shared experience — definitely including fun! — conversations have to happen.

#ccourses enables and encourages multiple streams of conversation — Twitter hashtag conversations, G+ Community conversations, aggregated blog posts at the course hub, and the forum.

One of those streams of conversation can help us make sense of the texts and webinars and makes. The other stream of conversation can help us improve our conversations on the fly. If you are interested enough in the possibility of persistent conversations and further co-learning units around connected courses, join the conversation Gardner Campbell has started in our forum.